By: Jessica Brown ![]() @Jessica_E_Brown

@Jessica_E_Brown

First published: Stories to Sit With – Independent, in-depth journalism

When your social housing legacy is left to the forces of London in the depths of a housing crisis, things can go one of two ways. Unless you’re Kate Macintosh.

After World War II, the government led a social house-building revolution that improved living standards for millions of people across the UK. But it didn’t last; by the 1980s, momentum was starting to slow.

In London today, the revolution is well and truly over. Many of the remaining council estates have been neglected, standing on their last legs until councils can justify knocking them down and replacing them with private housing.

What’s it like for the people who helped build London into an egalitarian idyll, watching these social housing safety nets, once at the forefront of architecture, go from sanctuaries to a living nightmare?

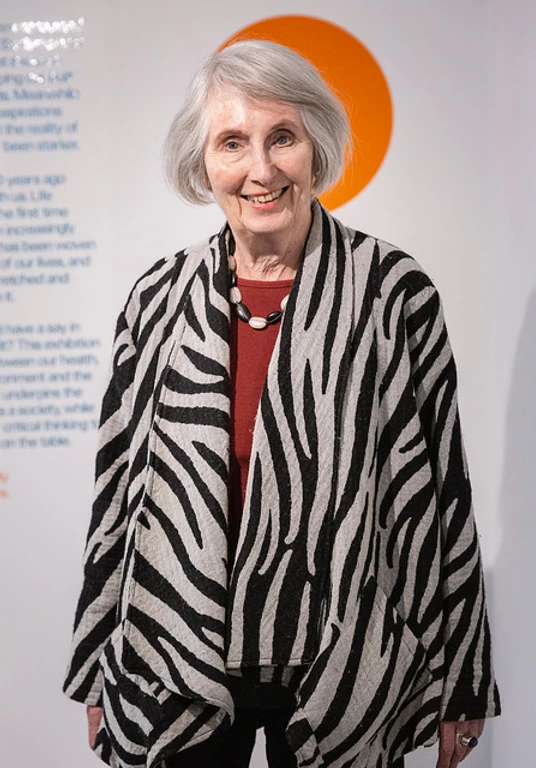

Kate Macintosh

The signs that Kate Macintosh would become a socially aware architect were there from a young age. She grew up in 1940s Edinburgh, where her father, Ronald, was head of the direct labour department of the now-defunct Scottish Special Housing Association, which provided social housing. He brought his daughter to building sites when she was a child and introduced her to a female architect, who were few and far between at the time.

She was the only woman in her year to graduate from Edinburgh College of Art with a degree in architecture, after which Macintosh worked briefly in Warsaw, Stockholm, Copenhagen and Helsinki, before heading to London. By the time she reached her late 20s, she was working in Southwark Council’s architecture department when she was tasked with designing Dawson’s Heights, a social housing block on a site in Dulwich, south London, on top of a hill four miles south of the river Thames, overlooking Primrose Hill and Crystal Palace.

Macintosh had been inspired by the sociological study, ‘Family and Kinship in East London,’ published seven years earlier, which examined cohesion among communities living in terraced houses in the East End at the time, and how this related to planning policies. She wanted to encourage integration between residents, so she designed access routes that would be shared by one-, two- and three-bedroom homes. She also gave residents shared green space, with no cars allowed in the middle of the building.

Macintosh was also encouraged by new government legislation designed to make homes more spacious. The Parker Morris standards for public housing made it clear that creating too much space was better than creating too little.

Dawson’s Heights

More than five decades on, those living in Dawson’s Heights can’t fault its design. James Rixon bought a three-bedroom, ground floor flat in Dawson’s Heights in 2014. He lived there for a few years with his wife, but when they had children they moved out to Cambridgeshire because they couldn’t afford the childcare. They rented out the flat at £1,700 a month, which is relatively low for the area. The lingering stigma of living on a council estate, it turns out, financially rewards those who overcome their prejudices.

“There’s still stigma attached to it – if there wasn’t, this flat would be the same price as a shit Victorian conversion on the same street. It suits me because it means we’re able to live here,” he says.

The Rixons recently reclaimed their flat; unsurprising, since Rixon is a chartered architect with a soft spot for social housing.

“We like it here so much, we didn’t want to live anywhere else,” he says.

Rixon says his flat is extremely light, and even on the ground floor, it has great views.

“Everyone’s got a big view of the sky,” he says. “The flat is compact, but the way it’s broken up, with a split-level, makes it feel larger than it is.”

“Architecture education is socialist,” he says. “They don’t teach you how to build to cram everything into the smallest space to make most money – it’s about how to create a better living experience. Of course, the real world is a whole different thing,” he says.

Presumably, Rixon isn’t counting Dawson’s Heights in this ‘real world’.

Nudging Cohesive Communities – Nothing New

Macintosh’s vision to nudge people into a cohesive community still plays out now: Rixon regularly sees elderly residents with whom he’s on a ‘saying hello’ basis, which is rare in London.

John Dignan also let out a three-bed flat at Dawson’s Heights, and when he came back from travelling three years ago, decided to move into the property himself.

“It’s just stunning,” he says. “My flat is remarkably quiet, and it’s very much designed with people in mind. If this was transplanted to Kensington, it’d be worth over a million,” he says.

There is one downfall: Southern Housing, who took over management from the council. Dignan struggles to get any response when he has a query or complaint. The grass is cut regularly, which Dignan appreciates, but he says the housing association seems to do the minimum it can get away with.

After Dawson’s Heights, Macintosh moved to Lambeth Council’s architects’ department, and was soon at the helm of 269 Leigham Court Road, a two-storey building of 44 sheltered flats for the elderly, which was completed in 1969.

“Sheltered housing at that time was the latest advanced thinking around how to accommodate the elderly in such a way as to encourage the maximum degree of independence and autonomy, while having a fallback support system which would kick in if the person developed additional difficulties,” Macintosh tells me.

She designed seven pavilions linked by a covered walkway, with 45 flats and an additional flat for a live-in warden. The site is relatively isolated, so Macintosh came up with the idea of having a corner shop on the street.

“The idea of putting a shop on the street front is an example of how open-minded the borough was. I took the idea to the housing manager and he immediately said ‘yes, put it in’, which is an example of the open, collaborative mode of working we had then.”

Social Housing on the Agenda

Social housing was high on the agenda when Macintosh built Dawson’s Heights and Macintosh Court. Under Harold Macmillan, the government built 300,000 houses – private and council – every year. Between the 1950s and ‘70s, almost 40 percent of architects worked for councils, according to Philip Boyle, an architect who works for Modernist heritage body DoCoMoMo.

“People used to say working for local authorities was boring, but it was actually really good because you learnt as you went along,” Boyle says. “Most architects in studios and offices had to get whatever work they could get, and the way architects work is that the client is always right.

“Kate did one building, learnt from it, and put those lessons into the next one. You didn’t have to worry when you were next working,” he says.

But Margaret Thatcher abolished Parker Morris standards two decades after they were implemented. Architects flocked from councils, and the social housing boom was officially over. After finishing 269 Leigham Court Road, which was another success for Macintosh, she went on to work for other councils outside London, before setting up a private practice with her husband.

Macintosh returned to Dawson’s Heights when she was interviewed for the documentary ‘Utopia London’, which came out in 2008, the year Macintosh retired. She was nervous the residents might hate her, she told the Architecture Foundation, but the adults hugged her and the children danced around her.

“When I visited for the shooting of Utopia London, it was the first time I’d been back for many years,” Macintosh says.

She spotted four caretakers on site – which has now been reduced to three – and noticed improvements, such as double glazing. Although, the pedestrian bridge Macintosh had designed on the site had been removed.

Macintosh has visited Dawson’s Heights several times since; she attended a summer party last year on the green. She tells me she received numerous messages over lockdown from residents thanking her for providing green space for them.

“They told me the green space has helped them overcome a sense of isolation, that they were encouraged to go out and clap for the NHS on Thursday nights and people were coming out onto their balconies and competing to see who could make the loudest noise.”

Thatcher’s Legacy

In the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher started starving local authorities of funds – a tradition that successive governments have continued – meaning they didn’t have sufficient funds to carry out routine maintenance on social housing.

“Thatcher offered to local authorities all sorts of bribes if they opted to have sites taken over by housing associations, promising benefits such as new kitchens and bathrooms,” Mactintosh says.

Dawson’s Heights took the government up on this offer, and the block was taken over by Southern Housing Group, who Macintosh says have maintained it reasonably well. She gets the overall impression people living there are very satisfied. The site’s success, she says, partially comes down to the proportion of leaseholders, who own their homes, which is around 30 percent.

“What often happens in local authority schemes, certainly in Lambeth, is that they deliberately try to divide and rule by appealing to their own tenants, offering a bright new shining house if they agree to be moved off the site so they can demolish houses,” Macintosh says.

“But the leaseholders feel rather differently – they’ve got savings invested in it, so they’d get a much worse deal. So if Southern Housing Group has tried that ploy it hasn’t worked. There’s a sense of community, of all being in this together.”

Leigham Court Road Revisited

When Macintosh revisited her work at 269 Leigham Court Road, however, it wasn’t to film for a documentary with ‘utopia’ in the title. Her vision, she says, had been abandoned; the site had been deteriorating for 40 years.

Lambeth council has been accused of ‘managed decline,’ which is where councils neglect a social housing estate until it’s in a bad enough condition they can justifiably demolishing it – and make a profit from replacing it with private housing – rather than carry out repairs.

“One logistical deterioration was the flat for the live-in warden. The idea was the flat would be very valuable accommodation and someone would be willing to work there at reduced pay and be on call, like a matron at boarding school,” Macintosh tells me.

Now, they have a ‘floating warden,’ Macintosh says, with a call system that doesn’t always work.

“God knows where it’s floating to when a resident falls down in the shower and the call system isn’t working,” she says.

Macintosh first returned to the site in the middle of a battle between the council and the residents. In 2013, Lambeth Council declared the estate unfit for purpose, but said getting it back up to standard would be too expensive. Instead, it said it would demolish and rebuild on the land, moving all 50 residents elsewhere.

Or, in the words of Boyle, “Lambeth wanted to make some money and build some newer housing, so they let it get run down so they could move everyone out”.

Social Vandalism

Macintosh said in a radio interview it’s ‘social vandalism to break up this thriving little community, where they need minimal help from outside because they help each other.’

The residents were indignant. They sought advice from Macintosh, who told them to get listed status for the building, so that Lambeth couldn’t touch it. They started an online petition, got hundreds of signatures from big architects, and presented it to English Heritage, who, in 2015, gave the building grade two protection.

“There was a great sense of celebration,” Macintosh says. “They hung out flags and there was a sigh of relief, and they had a party.”

The residents renamed the building Macintosh Court in honour of the architect who designed, and subsequently helped to save, their homes.

But their troubles were far from over. Lambeth sent a “very sulky” letter to residents, Macintosh says, in which the council stated that it didn’t agree there was any value in the development. But it had been forced into a corner, Macintosh says; they had no choice but to upgrade the residents’ homes.

The next thing Macintosh heard was that the council was going to spend £1.5 million upgrading the building. In 2017, Lambeth consulted Macintosh and other architects, as well as the residents, on how to spend the money, but their feedback was ignored.

Instead, subcontractors were hired to install a network of pipes on the outside of the building, which was illegal because the council didn’t have permission to alter the listed building’s exterior. While the work took place over the next two years, residents had to stay in their homes. Macintosh says she was ‘angry and distressed’ when she first saw the damage.

Material Vandalism

“I walked around and my heart sank at every turn,” she says. “I spotted a great array of pipes on the external northern walls. I took photos of it, and at a meeting in July 2018, I showed the council this photo and said, ‘Who authorised this? You do realise this is illegal work?’ Their jaws dropped.”

Residents’ possessions were drilled into, their hot water was shut off repeatedly, and they were potentially exposed to asbestos when, following the installation of new roofing, several residents’ ceilings started leaking. One resident had to sleep on a damp mattress in his living room for a month until his ceiling was repaired. Another resident was, until recently, sleeping in an armchair because his home was flooded.

“Quite apart from physical vandalism on a listed building, it’s abuse on elderly people by carrying out building works with them on site,” Macintosh says.

Residents say safety measures were ignored when the asbestos was removed – although the council says proper precautions were taken. A report by Men’s Aid charity found that the drilling and dust affected the health of those with respiratory issues – exacerbated by the fact the work prevented some residents from being able to open their windows – while the constant noise and vibrations affected many residents’ mental health.

The ordeal brought the residents closer together, they began sharing dinners and calling in to check on each other. Some were, and still are, bedridden, and were supposed to have care visitors coming in while workers drilled holes through their walls. At least one care visitor refused to come in them circumstances, Macintosh says.

Resident John Beechey says the contractors have made countless mistakes, even putting the radiators on upside down. Their homes have been ‘wrecked’, he says, but he doesn’t think the damage will ever be put right.

“They drilled holes into people’s flats for no reason,” says Janet Gayle, who’s been living at Macintosh Court since 2018.

“They’ve put in really inefficient, ugly and dangerous radiators and taken away a bespoke design that heated the whole home. They’ve threatened our tenancies. We’ve been told it’s not even sheltered accommodation anymore. Nothing is as it seems.”

DoCoMoMo warned that if the ‘illegal work’ wasn’t repaired, it would ‘make a mockery of Listed Building legislation, setting a disastrous precedent, and undermining the legislation’s fundamental purpose to protect the nation’s architectural heritage’.

An incompetent and Corrupt regime

Macintosh called it an ‘absolutely incompetent, if not corrupt, regime’, and a “litany of incompetence and failures”. She attended a meeting with Lambeth in November 2018, when the council had almost completed the work.

“They tried to persuade us they should give themselves provisional planning consent for this illegal work to avoid an enforcement notice, with the proviso they’d then appoint a firm to look at how things could be improved. We said, ‘No way, what sort of idiotic trap are you trying to lay for us here?’”

But none of the nightmares tenants have endured is a reflection on Macintosh, Gayle says.

“This was an absolutely beautiful place. Kate was relatively young to come up with something so progressive, she was really brave to peruse what she did. Most of the time, social buildings are designed to work for landlords, rather than the people living in them,” Gayle says.

“All the things Kate thought of to make this a comfortable place for elderly people to live has been completely disregarded.”

Gayle thinks the council has marked her and her neighbours as difficult residents for taking a stand against the illegal and dangerous work done to their homes. She suspects the council had hoped the residents wouldn’t fight back; and in some respect, it’s right.

Digital Excluded by Design

“Residents haven’t got the means to go on social media, there’s not much they can do. Most of them are between 80 and 90 years old,” she says.

The fallout from these repairs is ongoing; tenants currently have no fire extinguishers in the building. The council now intends to seek retrospective permission from itself for the illegal work, according to DoCoMoMo.

The warden is now nowhere to be seen at a time when they really need care – four residents have died in the last four months. Two residents are in the process of suing Lambeth, and Macintosh has offered her continued support.

“Kate’s amazing. She was down there with the tenants saying it shouldn’t be like this; she’s gone far beyond what architects normally do,” says Boyle.

She built an “extremely humane environment for people,” he says, and innovated where many others failed at the time. But revisiting Macintosh Court hasn’t been as validating an experience for Macintosh, as it is when she visits Dawson’s Heights.

“When I go to Macintosh Court, I come away really depressed. I feel such distress for residents continuing to fight on, but there’s a limit to what I can do, especially as I’m probably as old, if not older, as the residents now. At Dawson’s Heights it’s reversed – I feel uplifted and affirmed.”

Today’s Dawson’s Heights is one of the closest modern examples of what London’s architects had in mind when they envisioned their work being lived in. But her surviving legacy isn’t enough to fool Macintosh. The London of the 1960s ‘couldn’t be further away from the ethos we’ve got now’, she says.

“At that time, the atmosphere was optimism that things were improving for the majority of people in need. This reimagined regeneration ethos was there to cover the health, dignity and longevity of the population and raise standards. Once Thatcher came into power, that rapidly unravelled,” she says.

Even in Lambeth, which Macintosh describes as a once-outstanding borough, damage was inflicted and several beautiful estates were targeted to be demolished and rebuilt to meet the housing crisis.

“I didn’t see it coming, because it was so clear to me that what we were doing was of great benefit.”

The fallacy of ‘Affordable rents’ in London

Macintosh, now 83, is critical of how things are shaping out, and says the process whereby estates are knocked down and rebuilt with a proportion offered at ‘affordable’ rent is “a load of hypocritical rubbish”.

“It isn’t affordable, certainly for the indigenous population of Lambeth,” she tells me. “It’s forcibly decanting and evicting the working class of London.”

Macintosh can see parallels between now and the 1930s, when the government withdrew public support and safety nets for less advantaged people.

“We’re seeing the same now, we’re seeing a rise in cases of rickets, and children admitted to hospital with malnutrition,” she says.

Twelve years after retiring, Macintosh continues to advocate for communities on the receiving end of an ugliness in the system she could never have predicted. Her advice to people who are in similar positions to the residents at Macintosh Court, on the receiving end of councils who want to sell the land they live on, is to resist and stick together.

“I think the fightback has started, but we’ve just got to stick in there and resist. This government is so crazy, but I hope eventually it’ll do something so totally illegal there will be a collapse.”

“I’m doing my best within limited energy resources to keep myself informed and give advice,” she says.

Macintosh’s vision for cohesive communities that look out for each other has come to fruition in the good, and the ugly, that has spawned from her intentions all those years ago.

Dignan really appreciates the community spirit where he lives at Dawson’s Heights.

“I encounter various people in the building and generally, they greet me – which is unusual in London, where people don’t usually say hello and ask how you are.

“One time, a kid was playing football downstairs, and stopped me,” he pauses for dramatic effect, “To ask if I wanted help with my shopping.” He laughs. “I just had to post that in the Facebook page for residents.”

Author Bio

Jessica is a freelance features writer. You can find more of her writing at stories-to-sit-with.com, or on Twitter @Jessica_E_Brown‘

SHM Notes:

Headings added.