This is part of our WISH series of innovative women in housing. This interview features Aileen Evans, CEO of Grand Union Housing, who gives us an insight into her thinking of women in housing, innovation, and the future of housing.

Strange trajectories from musical aspirations to a career in housing

When asked about how Aileen got into housing, she shares a common observation that ‘housing is a career of destination rather than a choice’. This is a well repeated sentiment of housing practitioners who ‘found’ housing as a career and highlights its transition to a profession that people choose today. It is made more stark considering her aspirations to be a musician, aspirations curtailed by a lack of places for women in the brass section of orchestras. Her first role in housing was with Nottingham City Council, where she ‘fell in love with housing’ due in part to the variety offered by the role and the excellent training provided by the council. This exchange brought to mind how the professionalisation of housing may be a mixed blessing. Careers are individual projects and the passion for collective public work can be lost. I don’t think this is the case with Aileen and her passion for collective politics and building services from the context of tenants’ lives are reoccurring themes in our discussion.

Innovation in process, psychographic data and emotional understandings of tenants and place.

The conversation turns to innovation. Aileen describes a need for the sector to move on from a ‘sheep dip’ approach of treating everyone the same. She contrasts this with a commitment to area-based working, an approach seen in need of modernisation by many, with innovation associated with concepts such as patchless working. She describes how this tension is navigated by taking an area-based approach to the properties and varying the service around what tenants want in terms of their relationship with their landlord. She recognises that 80% of Grand Union tenants would like to be left alone. For the tenants who want extra help, services are there for them.

The complexities of variable demand have resulted in innovation in methods, with the completion of a psychometric survey to understand tenants. This asked nuanced questions about how tenants experience services and put the onus on Grand Union to change based on these findings. The challenges can small, such as changing communication style of letters and webpages. It produced bigger challenges as it found many tenants with health issues spend a lot of time in the home; an understanding that centres how important the home is in tenants’ lives. Aileen is clear that she does not want tenants to have bad experiences of home, or ‘experience bad lives in a good home’. My reflections turn to the challenges of navigating this space, psychographic data is deeply personal by its nature; Aileen emphasises that Grand Union do not keep personal data on tenants but work with the findings. This captures to some extent the challenges posed by innovative knowledge production; how to navigate simplified and deductive data produced by such analyses with the varied and dynamic nature of complex lives lived from a home.

An interest in area-based working and tenant relationship’ with the place of home creates a groundwork for innovation in building services based on an emotional understanding of home. This is a line of innovative thinking that stands in contrast to other approaches that centre hyper-rational and reductive technology driven approaches. It will be interesting seeing this work develop.

Imagining the future of housing – connecting a tenant-centred understanding of home with the politics of housing provision

Aileen turns the conversation to Grand Union’s commitment to build more social rented homes. In England, this is a challenging stance to take, as affordable builds for rent and shared ownership sale are the current political flavour. She describes taking a tenant centred approach to understanding home affordability. This approach reveals stark facts, some homes cost 1000 pounds a year more to heat than others. This analysis raises questions about what is meant by the term ‘customer experience’ as an experience of housing services is very different to the experience of the home as place. A place-based understanding of home speaks more to public policy than business efficiency that turns the conversation to the wider politics of social housing provision. Aileen is optimistic that a political case can be made for social housing. The strain caused by the dominance of private renting, and the cost efficiencies that are produced in the long run for the taxpayer by providing safe, warm, and affordable homes add up to a reasonable demand for more social builds. My thinking is more cynical as it seems a nation of private landlords has a political utility in providing a divisive status quo. Aileen’s optimism for a better future for housing in the UK is essential, as imagining future change is a key step to making it happen.

From retro-sexism to modern day diversity challenges. How housing can innovate with diversity

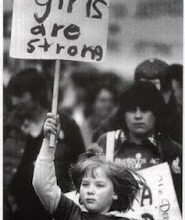

We turn to discuss Aileen’s experiences as a woman in social housing. Maintaining a positive outlook, she describes never having felt like she’d missed out on a job or been particularly impacted by virtue of her sex. She does describe experiences of challenging how she has been spoken to, or behaved towards by the odd sexist man she has encountered. She recounts the difference between housing now and in the old days, where nude calendars were the unquestioned norm, and she was once grabbed by a senior officer. My thoughts turn to a tendency of women to downplay and normalise inappropriate behaviours, many of us, if we stopped and thought about it, can list double figures of problematic interactions and behaviours that add up to a negative, sexed experience with the world. It’s good to hear how much has changed, although I wonder if I would be speaking to a different person if Aileen had been able to pursue her original dream of performing in an orchestra, a dream that was shut down by the assumption women could not play in the brass section.

Our conversation makes me reflect on the feminised history of the housing sector. Back in the early days of social housing, Octavia Hill favoured women housing officers and there is a trend for customer facing working to be undertaken by women, and property work by men. Aileen responds to this observation that this is not the case at Grand Union, there is a 60/40 split in property roles, with more work is planned to recruit women maintenance operatives. She widens the topic to include broader issues of diversity, Grand Union has 18-19% BaME working staff which is impressive considering an area population average of 4%. She recounts being given a list of possible candidates for a job that was all white males and returning the list, asking the recruiter to ‘do better’. She acknowledges there is more work to do regarding employment access for people with disabilities. If she takes as proactive an approach as she has with race and ethnic diversity, I am sure she will achieve this aim. The sector houses a significant number of people experiencing disability and health inequalities and this suggests that there is an opportunity for innovation in recruitment and retention practices in social housing work.

Personal motivations for driving social change

We revisit and discuss her motivations for building such a strong strand of social justice into her approach to leading Grand Union. She is highly motivated by childhood memories of the injustices she and her family experienced due to her father’s participation in mining strikes. She crafts a picture of a man whose opportunities to be other than a miner was curtailed; a man who campaigned passionately for the preservation of a job he would not have chosen, but was important to him, his family, and the local community. She describes the abuse her mother received on the street for being Irish. This was the peak of ‘the Troubles’ and being accused of being a terrorist must have been a painful experience for her mother, and for her family to witness. My mind turns to a PhD peers research into Muslim women’s experiences, and how the spectre of terrorism is still used to other, and hurt people we have more in common with than differences. Aileen connects these personal experiences with the important roles housing, health, education, and a general sense of security and stability play. She believes the state has a responsibility to provide as a baseline these stability providing essentials, so people can flourish and grow. I am reminded of my own research that touches upon the psychology of poverty. This framework emphasises the importance of stability in relieving psychological harm. It is a strange location to be in nowadays, making a case for contextual stability when the popular discourse is one of rugged individualism combined with a moral responsibility only to oneself and family, not others that you don’t know and may not even like.

Imagine a better world and take the small steps to make it happen

It’s clear that Aileen is passionate about a better world, she is a big believer in doing what she can to change things, it may seem futile but little actions, even when the tide is against you, have ripple effects. If we work on these little actions, and the context we take these actions in, maybe we can change the tides. We conclude our discussion about our views on the moral complexity of ‘doing good’ and how this can be done without imposing a paternalism that seems to be built into the sectors DNA. I’m left optimistic at the end of interviewing Aileen. Housing is not a perfect sector, far from it, but I think it’s a better place for having people like Aileen in it who are passionate about housings role in contributing to a good life, as opposed to the dominant idea of it being a financial investment. Safe and secure housing is about investing in people and place, and the ensuing profit is happiness and hope for a better future.

We thank Aileen for her time to speak with us, it was a pleasure!