By: Stuart Hodkinson ![]() @stuhodkinson

@stuhodkinson

We are pleased to publish an extract of Stuart Hodkinson’s book Safe as Houses. In this book, Stuart uncovers the story behind Grenfell. How could it have come to this? Working closely with resident groups, Stuart gives a detailed account of all that is wrong with outsourcing, private finance initiatives, and councils turning a blind eye. In this extract from Chapter 3, we hear the horrifying story of Edward, a council housing tenant whose home was supposed to be refurbished under a private finance intiative (PFI) scheme.

By the summer of 2005, 15 years after Edward and family moved in, Partners and United House began conducting surveys of all council-owned houses in his street ahead of refurbishment under PFI. In this close-knit neighbourhood, word quickly spread of resident disquiet with how these surveys and the works that followed were being undertaken. ‘So I carried out my own survey of nearby tenants who had scaffolding outside their homes and horrific stories emerged.’ Edward’s neighbours complained of ‘children’s beds falling through floorboards during the works, front doors left open, incompetent workers, damage to possessions, severe distress, and people going to the doctors to be treated for anxiety’.

These experiences mirrored the high-profile problems affecting the scheme and regularly appearing in the local press. Edward took his survey findings to the Partners PFI Residents Forum, which met every few months in Islington town hall. He raised concerns about the potential impact of the planned works on his severely mentally disabled son and sought specific assurances about health and safety. In total, more than a dozen pre-work talks and meetings were held with Partners to agree an efficient and safe schedule and conduct of work.

However, just two days after work finally started, in September 2005, Edward was shocked to find that workers had left several two-inch rusty nails sticking out near the bath, and had left more of these nails protruding from the old floor after they had removed the covering. This rendered the bathroom dangerous. Believing that health and safety laws and residents’ welfare were being recklessly flouted, Edward photographed the hazards and uploaded them to a website to ensure that other residents were informed.

He also told Partners that the workers who had violated his family’s safety would not be allowed to re-enter his home. When other workers just a few days later failed to use dust sheets and covered family belongings with dust likely to contain asbestos he demanded a meeting with a senior Partners manager. In response, Partners informed Edward ‘out of the blue’ that the family would no longer be allowed to stay in the house during the works, claiming that structural surveys had revealed the need for more intrusive inspections and works to the floors. However, Edward believed this was a cover story to get him out of the way:

They realised that with me living there, I was going to watch and document every single act of vandalism and sub-standard work. I was going to make them do a proper job. And that’s not how PFI works, it’s not how these unmonitored sub-contracting chains work, and they were determined to get me out.

Fearful of what they would do to his home and the emotional toll that moving into temporary accommodation would have on his son, Edward refused to leave until he was provided with a schedule of proposed works and a clear statement about the time they would take. Partners claimed this was impossible due to the impracticality of surveying the home while the family was living there, and instructed Islington council to serve a ‘notice seeking possession’, threatening the family with permanently losing their home if they did not move to temporary accommodation.

By now, Edward’s health and family situation were rapidly deteriorating: ‘due to the stress and anxiety imposed on me, I found it ever more difficult to care and support my son as his mental health got gradually much worse’. After an 11-month battle to agree a ‘decanting’ agreement, a removal firm packed up their belongings and moved them to a temporary home in October 2006, which they were advised would be for four months. Yet despite the urgency with which they wanted Edward and family to leave, Partners and United House nailed corrugated iron on all doors and windows and left the home empty for nearly three months. In fact, building works only started after a small demonstration organised by Edward and local residents outside the town hall.

In February 2007, Partners informed Edward that all building works were ‘complete’ and the family could now move back home. Before taking them at their word, Edward made a request to inspect the refurbished home, which was granted. He vividly remembers the ‘carnage’ awaiting him:

Rather than repair and improve the property, the building works were incomplete, shabby and in some places dangerous. Everywhere was covered in dust and debris. Previously nicely decorated walls had massive holes and beautifully varnished Georgian floorboards had been scratched and damaged with nails sticking out where floorboards had been lifted. As I inspected the basement a piece of plasterboard actually fell on my head and arm.

There were clear signs that a major flood had occurred in the room above the kitchen, causing them to rip out my beautiful high-quality timber suite and replace it with cheap ill-fitting units which literally fell apart as soon as you opened drawers. The new kitchen layout had left the wall cupboards virtually inaccessible as you now had to stand on chairs to reach inside them. The paint on the walls rubbed off on cloths and clothes as they had used unsuitable emulsion unfit for kitchens given the condensation.

They’d placed power sockets in such a way that normal kitchen appliances couldn’t be readily plugged in and used, creating an increased health and safety risk. In several rooms floors were giving under pressure; it felt like being on a bouncy castle. The springiness of the kitchen floor was so bad that you could overturn a pan of boiling water just by gently walking up and down. The new boiler flue hadn’t been cemented in, while boiling-hot water came out of the garden water tap. I was heartbroken.

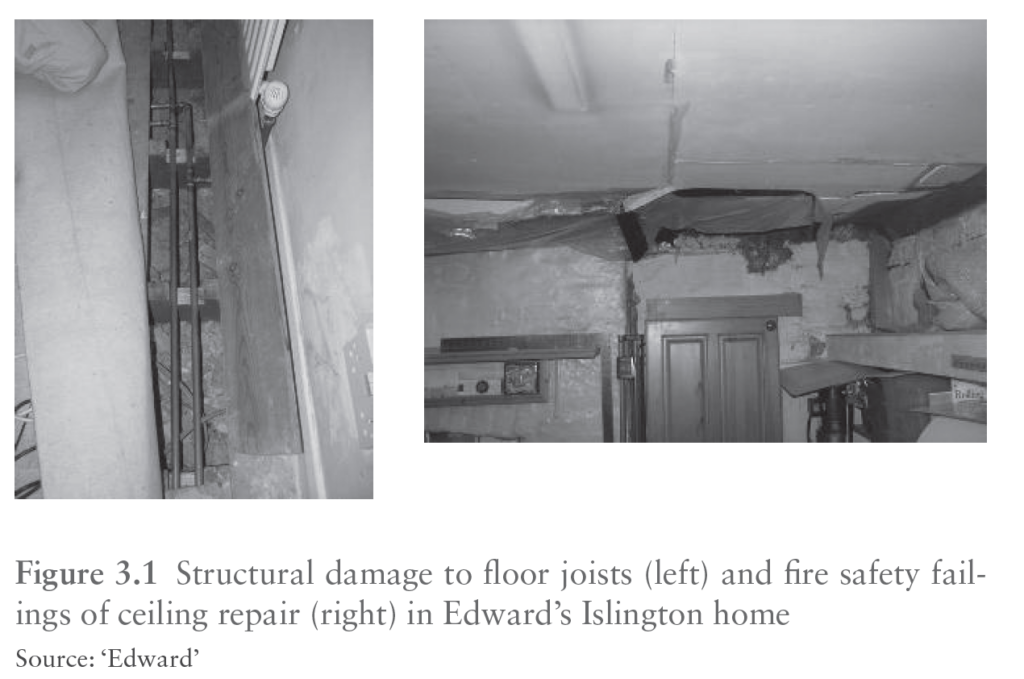

From Edward’s knowledge of building regulations, and gas, electrical and water safety, he believed that the works were dangerously defective (figure 3.1), and broke the law in multiple ways. He submitted photos and a complaint to Islington but was told that the work had been signed off and was ignored. Partners threatened Edward with costs and court action if the family did not ‘ready themselves to be transported’ home. Despite the property clearly now failing the Decent Homes standard and knowing that moving their possessions back in would make it more difficult to rectify, Edward was so afraid of losing his family’s home that he agreed, under duress, to return in early March 2007. He then set about proving that the works were dangerous and needed to be put right.

He immediately called in Corgi gas safety inspectors, who found the works carried out to be seriously defective and a ‘risk to life and property’. They disconnected the gas supply in order to prevent explosion and issued an enforcement notice against United House. Edward then called in Islington council’s own listed-building officer, who compiled a long list of breaches of listed-building regulations and laws. An inspection carried out on behalf of the water safety regulator identified 33 breaches of water safety legislation, prompting an enforcement notice against Islington council. An electrical safety inspector jointly appointed by Islington and Edward found 26 breaches of electrical regulations, causing category 1 hazards under the HHSRS system (see chapter 1). After input from several pro-bono architects and various friends in the building trade, Edward submitted a document that itemised 180 defects and omissions from the works.

The most serious of these was the massive structural damage caused by United House’s contractors cutting through and undermining a third of the house’s joists when installing the new central heating radiators and pipes. After conducting an inspection, the council’s own conservation officer informed Edward that much of the work done had been undertaken ‘without listed-building consent’ and was therefore potentially a ‘criminal offence’, adding that some of it was ‘downright dangerous’ and should be ‘attended to as a matter of extreme urgency’.

But Partners did not act urgently. Several months went by before Partners would even agree to inspect the work, and it took the company nearly a year to accept that something had gone wrong and agree to rectify some of it. In the meantime, the dangerous kitchen and bathroom floors were temporarily stabilised with acrow props while Edward waited for the structural damage to be corrected. His disabled son’s ground-floor bedroom had been made uninhabitable as the first-floor bathroom was above it.

As a result, mental health services had formally notified Edward that the home ‘was no longer suitable to provide care’ for his son, who was shortly afterwards sectioned and detained in hospital under the Mental Health Act. As we will see in chapter 5, a protracted legal dispute then took hold that lasted nearly seven years. An eminent surveyor, Stephen Boniface, was appointed as the court’s single joint expert to investigate the alleged breaches. Boniface’s subsequent report, in 2009, upheld almost every single one of Edward’s schedule of 180 defects and omissions, and concluded:

The work does not meet the requirements of the building regulations and by implication this therefore means that they do not meet British Standards or the requirements set out by various regulatory bodies. [It has] been carried out to an unacceptable sub-standard and extensive work is required to deal with the defects and problems identified.

However, it would take until 2014 for the main repairs to Edward’s home to be completed. What had begun as a Decent Homes improvement plan to simply rewire the electrics, install a new boiler, repair a couple of roof slates and renew the bathtub, originally estimated to take two months, ended up taking nine years. Partners had been paid £31,000 by Islington for wrecking this grade II listed building. Edward never received a penny of compensation or even an apology for what he and his family had been put through. As he told me a few years later, ‘while I am grateful that my health just about held out, the same regrettably cannot be said for my son and that is really unforgivable’.

Stuart Hodkinson is Associate Professor in Critical Urban Geography at the University of Leeds. We thank Manchester University Press for allowing us to publish this extract. Please follow this link to find Stuart’s book: https://manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/9781526129987/